Ever since Qatar was announced as the location of the 2022 FIFA World Cup, the country’s coverage in the world media has skyrocketed. The media is heavily scrutinizing FIFA’s choice of Qatar as the host due to the country’s ongoing human rights violations. While many argue that hosting the event in Qatar risks perpetuating the nation’s pre-existing issues, the increased media coverage has arguably led to some positive change.

Human Rights violations aplenty

According to a 2020 Human Rights report, serious infringements on human rights are taking place in Qatar. Among other issues, the nation still persecutes LGBTQ+ people and prohibits freedom of expression (including the right to assembly). Furthermore, inadequate labour laws and discriminatory policies and customs against women prevail in the country. Many of these issues share the same root cause—the restrictions on free and fair elections.

In particular, Qatar’s labour laws—or rather lack thereof—has been pulled into the public eye. According to the Human Rights Watch, the formation of labour unions is strictly forbidden, and migrant workers experience severe limitations regarding freedom of movement. Furthermore, numerous reports have echoed evidence of forced labour. The Human Rights Watch argues that this is due to Qatar’s problematic Kafala system, tying employees to their employers and thus opening itself to a pattern of systemic abuse. Migrant workers, who make up approximately 95% of the workforce, are among the most exploited. Indeed, several accounts have been given of an unsustainably low minimum wage, inhumanely long working hours, physical abuse and even penal servitude.

The troublesome situation at Khalifa Stadium

Unfortunately, the migrant workers building and refurbishing the Khalifa Stadium ahead of the 2022 FIFA World Cup are not exempt from these poor labour conditions. According to Amnesty International, the workers are faced with appalling living conditions, false promises regarding salary and even the confiscation of passports. Workers attempting to leave risk being threatened or reported to the police. As Deepak, a metal worker at the stadium, shared with Amnesty International, “my life here is like a prison.”

This situation, unsurprisingly, has led to much controversy. Sharan Burrow, the General Secretary of the International Trade Union Confederation, has repeatedly advocated for FIFA to back out of their agreement with Qatar and to choose another country to host the 2022 World Cup. In an interview with CNN, Burrow states: “these men are basically slaves there. The legal system doesn’t work”. She further emphasizes how the Qatari government has “no commitment to human rights”.

In response, FIFA issued a statement saying that “the World Cup in the Middle East offers a great opportunity for the region to discover football’s power as a platform for positive social change.” Qatar’s Supreme Committee, the state’s coordinating organisation for the World Cup, maintained a similar position, claiming that they want to “ensure a lasting legacy of improved worker welfare” and with the FIFA World Cup acting as a “catalyst for improvements”.

A potential silver lining

These statements by FIFA and Qatar’s Supreme Committee raise the question whether such positive change is not only possible, in light of the current human rights situation in the country, but if it is actually taking place. While the way ahead is undoubtedly long, it seems like there have been certain improvements. Qatar introduced significant labour reforms in September of 2020: migrant workers are now allowed to change employers if they give adequate notice and Qatar has raised the minimum wage. While these steps point in the right direction, many troublesome aspects of the Kafala system remain. Employees are still tied to their current employer and can have their visa revoked. Additionally, leaving without notice remains a punishable offense, labour unions and strikes are still prohibited, and passport confiscation and heavy indenture upon contract termination remain commonplace.

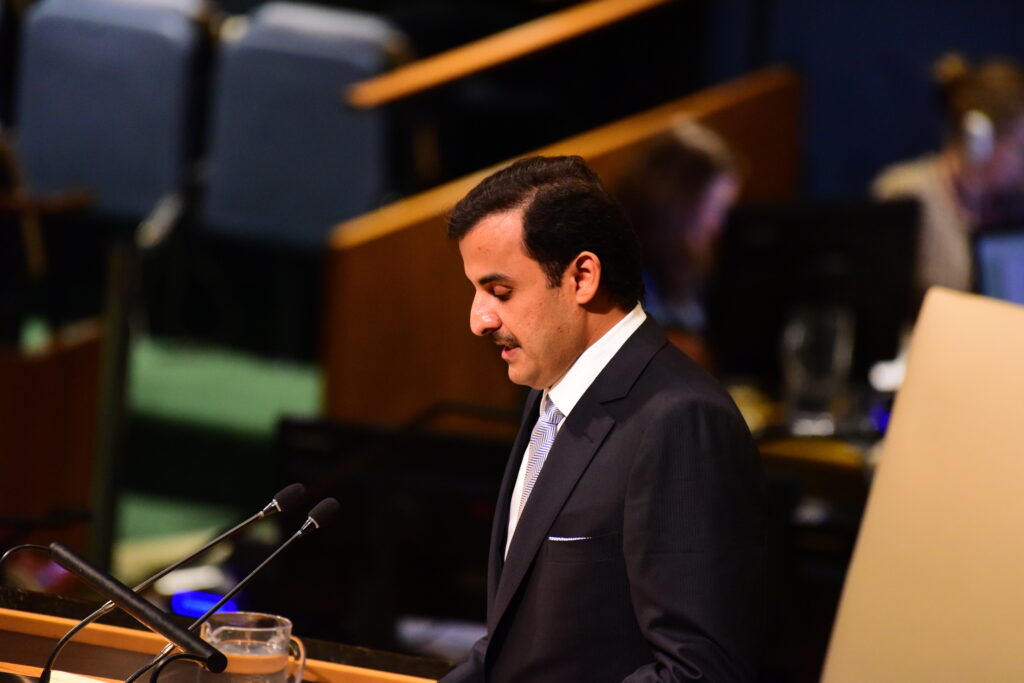

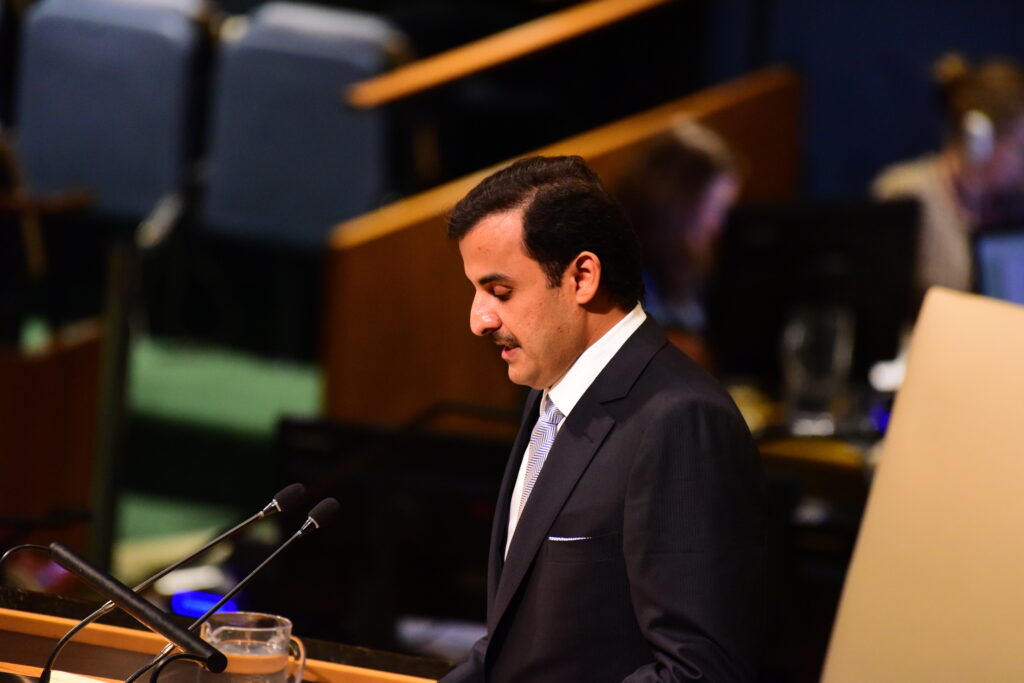

In October of 2021, Qatar had its first legislative elections. The initial legislation permitting electoral law was passed 18 years ago in 2003, however, it has yielded results only now. As such, these elections can be seen as a direct response to the spotlight pointed at Qatar due to the 2022 FIFA World Cup. However, this change is not as democratic as it seems: only third generation Qataris were eligible to vote, and only two-thirds of the country’s national council were elected. Additionally, while the council holds legislative powers, political parties are still forbidden, and the Emir has absolute control over defense and economic policy.

A nuanced picture

Ultimately, the reality is nuanced. While some positive changes have occurred in Qatar following the increased media coverage in light of the 2022 FIFA World Cup, the country still has a long road ahead when it comes to human rights improvements. Finally, FIFA’s real motivation behind hosting the 2022 World Cup in Qatar can be questioned: Is it truly in an effort to improve Qatar’s labour laws or is it the large profits FIFA stands to make from this collaboration? Either way, it is important to remain hopeful. While progress may be slow, Qatar is moving in the right direction.

Catherine Ekström