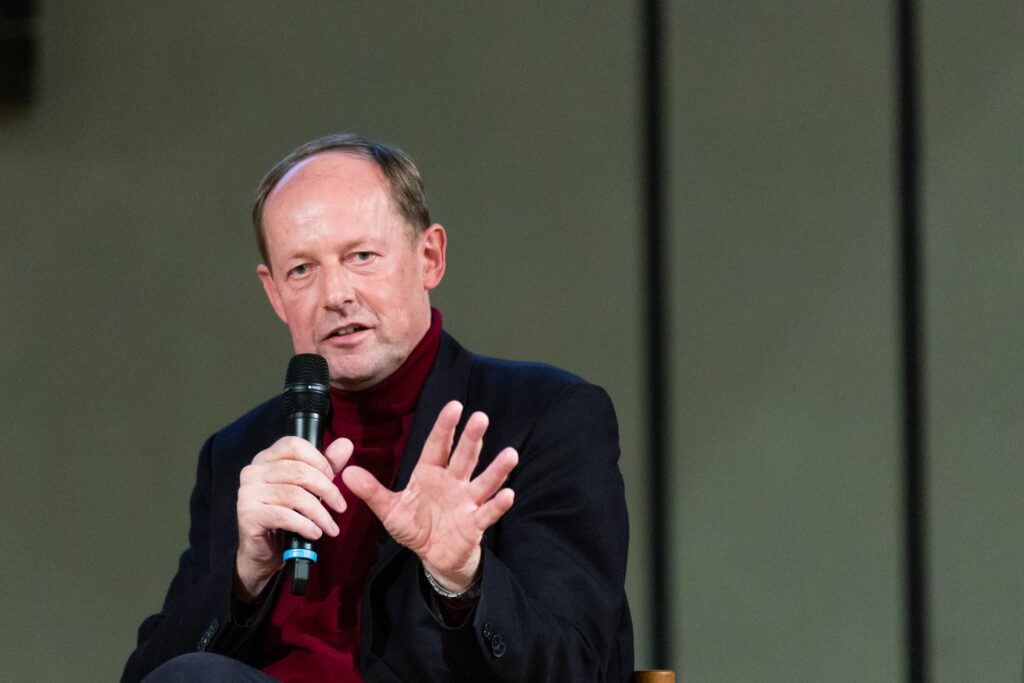

An Exclusive Interview with Prof. Dr. Frank Bajohr.

With antisemitism on the rise in Europe, issues such as memorialisation, the handling of perpetrators and revisionist history are all hot topics of discussion. UPF explored these themes with Prof. Dr. Frank Bajohr, Head of the Centre for Holocaust Studies at the Institute of Contemporary History, while in Berlin in November 2021. During the interview, Professor Bajohr explained the relevance of Holocaust research within foreign affairs today.

“The centre was established to be a forum for international research on the Holocaust and as a bridge to Eastern Europe in particular” begins Professor Bajohr. The first of its kind, the Institute of Contemporary History (Das Institut für Zeitgeschichte) was created shortly after the end of the Second World War in 1947. The centre for Holocaust Studies, however, was founded much later in 2013 after growing demand and need for a specialised department in this field.

Since then, the institution has joined with 24 others throughout Europe under the European Holocaust Research Infrastructure (EHRI) which is financed by the European Union. Its aim is to foster and strengthen international research as well as education and remembrance. Professor Bajohr emphasises the importance of nations working together when dealing with politically sensitive history as there are “dangers in a selective memory” when nations are left to do so as they please. Collectively, they piece together the fragmented history surrounding the Holocaust into an academic, peer-reviewed standard.

After a short reflection, he gives examples of Poland and Hungary. “The governments have an interest to emphasise, and I would say to overemphasise, the roles of Poles and Hungarians in rescue activities, in the rescue of Jews. To give the impression that the whole nation had been a nation under the German occupation, a nation of heroes, victims and martyrs, and there was nothing in between.” Indeed, one could argue that the two nations go further than just shifting or changing national narratives within public discourse, but actively prevent the publishing of research that counteracts their self-created image. For example, Poland has carried out legal cases against historians who produce material on the nation’s collaborative role during the Nazi occupation in the murder of Jewish people. The aim is to humiliate, de-credit and prevent others from pursuing similar work.

Professor Bajohr emphasises that these nations are by no means alone in their retelling of national histories. He warns that it is essential for the international community to continue the research of historical events in order to “prevent memory and memorialisation [Editor’s note: different forms of commemoration] from becoming selective and used for nationalist purposes or a nationalist narrative”. Of course, as a German who has spent his entire career researching how nationalist narratives can unfold, he understands the dangers on a personal as well as academic level.

Interestingly, Professor Bajohr also warns that the current, historically accurate memorialisation of those murdered during the Holocaust also poses a potential threat to the international community and to democracy at large. He explains that “you always see the same phrases, the same wording, the same witnesses, the same stories.” This routine creates a form of “static ritualisation”, explains Professor Bajohr. He would prefer to see a shift to the inclusion of not just survivors’ stories, but also those of perpetrators and bystanders. By diversifying the way we memorialise, we allow people today to understand the full complexity of the Holocaust, and in turn, stop oversimplifying contemporary socio-political situations.

Germany has been on its own socio-political journey when it comes to recognising the loss of Jewish lives during World War Two. Professor Bajohr reflects on his own childhood and explains that “there was no comparable memorial culture in Germany at that time.” Fallen German soldiers were the focus of both families and education. Today, however, the German government and society have incorporated memorialisation and remembrance into all aspects of society. From classrooms to monuments, within the last few decades, German citizens will have come in contact with the topic of the Holocaust in an institutionalised way.

Furthermore, Holocaust denial, an antisemitic conspiracy theory, is illegal in Germany. This provides some relief to Professor Bajohr as, through his role as Head of the Centre of Holocaust Studies, he attracts much online hate and antisemitism from such communities. He explains he diligently hands over cases to the police, which allows him to focus on what he really cares about—his work. Other legal roles within his work, he explains, includes serving as an expert witness in legal trials. Germany still conducts trials of perpetrators despite their old age. To some, this seems pointless. However, the symbolic gesture of German law enforcement shows a commitment to learning from mistakes. Professor Bajohr reminisces that he served as an expert witness at the trial against Oskar Groning, the so-called ‘Book Keeper of Auschwitz’ conducted in 2015. “A very well known trial.”

Yet, Professor Bajohr is aware that not all Germans are in agreement with such political intervention. There has been a growing number of German neo-Nazis, which has raised concerns about rising right-wing groups across both Germany and other European nations. He describes people joining such groups as “right-wing populist people [that] are developing a very specific variant of truth.” But Professor Bajohr warns that “you have to cope with this and you have to face the challenges […] the answer cannot be [to] stop all your [research] activities” because this would exacerbate the growth of right-wing movements and conspiracy theorists. He expresses concerns about the rising media and political attention such groups get rather than emphasising further education and research into the roots of what could allow for a future Holocaust to unfold.

Professor Bajohr’s overall message is the importance of education surrounding the Holocaust as a weapon against both antisemitism as well as broader, right-wing movements threatening democracy today. He imparts the power of knowledge and expresses hope that with continuing international research and collaboration, an event like the Holocaust should not be able to occur again. Although many feel that they have no responsibility to do this, Professor Bajohr asks that we all work towards a better world together. “I am not personally responsible for what has happened,” he says, “but I am responsible for the future.”

Philippa Scholz