When we think about unresolved geopolitical conflict dividing a country, we often picture distant disputes concerning regions such as the Middle East. However, we face the same kind of struggles in Europe—one instance being the island of Cyprus. Located in the Mediterranean, neighbouring Greece, Egypt, Turkey and Lebanon, the island has been of high importance for decades concerning trade between Europe, Asia, and Africa. Nowadays, Cyprus is also known for being a touristic hub where one can enjoy the sun, sea, amazing gastronomy and one of the oldest Mediterranean cultures. But if you decide to take a trip across the island, you might be stopped at the United Nations (UN) buffer zone dividing the Greek side of Cyprus from the Turkish one. Since 1974, this historical division has been affecting Cypriots who once cohabited peacefully. This article explores several recent issues resulting from this complex geopolitical context, and presents possible paths towards harmony on this divided island.

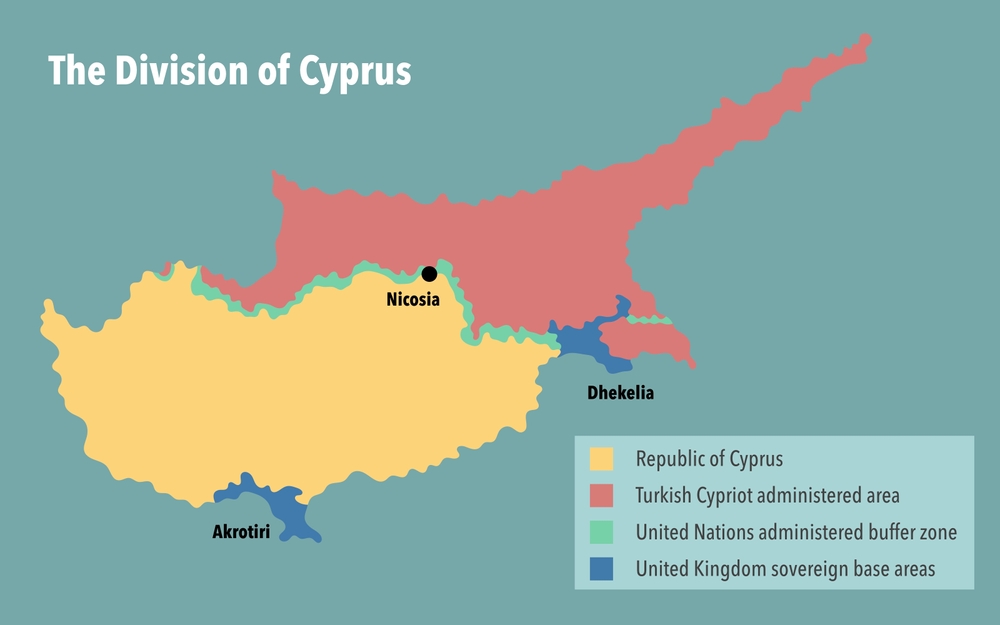

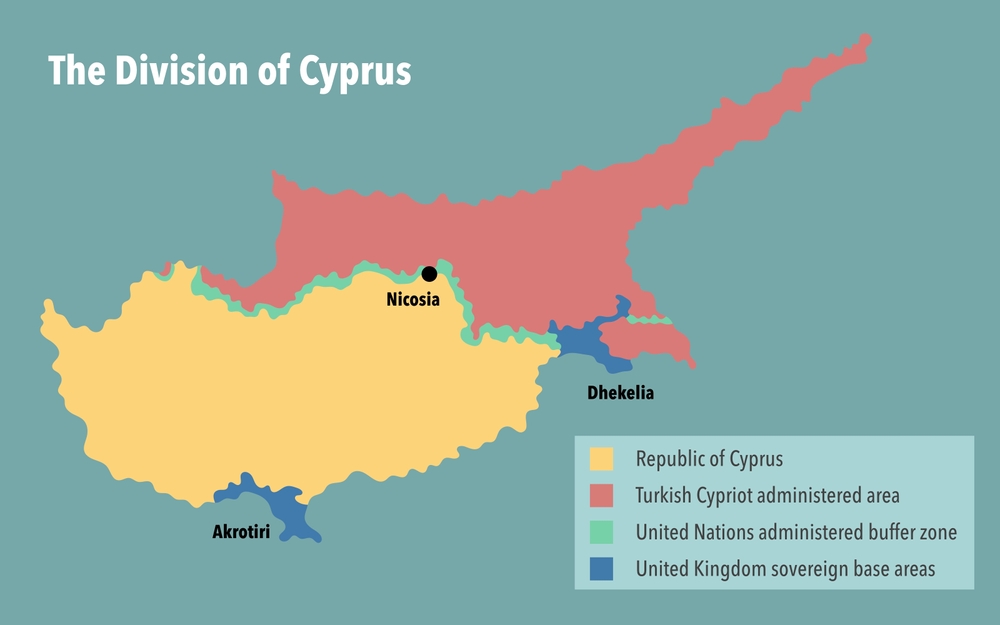

For a better understanding of Cyprus’ current geopolitical context, we have to go back to 1960, when the island achieved independence from the British Empire. After this, two UK sovereign bases were created on the island coast to be used as military bases and keep access to this strategic location in the middle of the Mediterranean.

Adding to this first division, Greek Cypriot nationalists intended a coup to take over the country in 1974, displacing more than 25,000 Turkish Cypriots. As a response, Turkey invaded the island five days after to capture Northern Cyprus for its fellow citizens, displacing over 150,000 Greek Cypriots. This war ended up dividing the communities and sovereignty of the island between the internationally recognized Greek Cypriot government and the self-declared Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus (TRNC). Those two conflicts led the UN to interfere with the installation of a 180 km long buffer zone, the so-called Green Line, to prevent any further invasions and coups after the events of 1974. This measure was also introduced to reduce tensions between the Greek and Turkish communities of Cyprus caused by these wars. Intended to be temporary, the Green Line became a permanent element of the Cypriot landscape. The United Nations Peacekeeping Force in Cyprus, UNFICYP, is now responsible for the defence of this large border.

Since then, millions of people have lost not only their homes, traditions and landmarks, but have also had to start a new life in the part of the island where their ethnicity and religion are accepted. Crossing this buffer zone is a harsh experience: places such as Famagusta, the former touristic highlight of the island, are nowadays reduced to a ghost town with empty degraded buildings. This area has been abandoned since the evacuation of Greek Cypriots in 1974, and it now belongs to Northern Cyprus, controlled by the self-declared TRNC which is slowly opening up remaining beaches for Turkish Cypriots.

While stories like these are tinted by sadness, anger is one of the main feelings fueling both sides of the conflict. As a matter of fact, the UNFICYP reports approximately 1000 incidents each year around the Green Line. Disputes often arise from illegal border crossings which are the result of a feeling of injustice on both parts concerning territorial sovereignty. Those conflicts are representative of how the division is only partially effective, preventing a move back to normality.

Indeed, conflicts around the buffer zone have increased since the Green Line was implemented. The Taksim Field is one of them: before the division, this football field near Nicosia, the capital, hosted many Turkish sports competitions. However, it is now part of the buffer zone. Turkish Cypriots, represented by the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus, or TRNC, pressured the UN to reopen it. After working on the self-declared opening despite Greek disagreement, TRNC tried to access the field but was denied doing so by the UN Peacekeeping force since it constitutes an illegal border crossing according to international law.

Tensions concerning the buffer zone’s location are illustrated in Athienou, one of the four villages located within the Green Line. New barbed wire is supposed to be set up around the village which is situated in the Lacarna district, near Nicosia. According to the authorities, this measure follows the renovation of the police zone in this area to increase security, limit illegal migration and protect Greek Cypriot land. However, the local community disagrees with this measure: even if some of them still do not feel secure due to the proximity to Northern Cyprus, most of them see the barbed wire as an obstacle to peace and freedom of movement.

Another symbol of this ongoing division is Varosha, the former touristic neighbourhood of Famagusta which used to be a famous holiday destination and has now been turned into occupied military land in the middle of the ghost town. After the Turkish army’s 1974 destructive bombings to take over the area, the TNRC is working on its restoration at a slow pace since Erdoğan announced in 2021 that “3.5% of Varosha would be open to the public as a pilot project”. This measure raised a lot of tensions since the UN resolution of 1984 only allowed its original habitants who fled the war to resettle in this neighbourhood. TRNC makes use of this ongoing military occupation of properties to negotiate recognition of the self-government as a state.

Moving on from these conflicts, some villages show us that peaceful cohabitation is possible, as for the village of Pyla located in the Lacarna district. Here, Turkish and Greek Cypriots still live side by side. While military threats intensify in other parts of the buffer zone, a third of Pyla’s inhabitants are Turkish Cypriots who refused to withdraw into enclaves in the 1960s. This special village resists ethnic segregation and is protected by its location within the UN buffer zone near the British bases. This “fragile balance”, according to its mayor, is not easy to keep, but it keeps on improving.To add to this increasing hope, new crossing points have opened since 2003. Three are located around the capital, Nicosia, and two others at the east and west of the buffer zone.

In November 2018, two further crossing points opened. These will enable inhabitants to move more easily between the two parts, also increasing the intra-island trade. However, in the same year, a gas dispute escalated tensions after a Turkish violation of the Greek Cypriot maritime Exclusive Economic Zone. The European Council closed the case in 2019, encouraging negotiations between the two sovereignties for drilling gas while condemning Turkey to several economic sanctions and suspending some contracts between the country and the EU.

While the threat of another war seems less present today, tensions and resentment still run deep between the Greek and Turkish sides. Aligning with international community efforts, the recent proposition from the Greek Cypriot government to send a rescue team to Turkey has been refused by the country suffering from a recent devastating earthquake, as a sign of their self-sufficiency.

This complicated geopolitical case shows us the impact of such a prominent division used as a tool for gaining political power at the expense of the population ending up developing hatred and traumas, losses due to the wars and tensions affecting their daily lives. However, hope is there, and some communities show us that those different populations can still live together despite the difficult obstacles that an administratively and politically divided country imposes. While this human-made boundary is argued necessary to protect inhabitants of Cyprus, one can wonder if it is not also at the core of the issue.

By Anaïs Colin