Water. The most precious resource on earth. Without it no life is possible. In some areas, water is becoming increasingly scarce. This puts humans, animals and the ecosystem in danger. Water, while taken for granted by many, is considered the “blue gold” by others. Its mismanagement can have devastating effects on our lives.

In Central Asia, blue gold is scarce and its bad management is the origin of many tensions and problems in regions where the supply does not meet the demand. In fact, Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan, which were once part of the Soviet Union, had fewer tensions when Moscow maintained the infrastructures and water flowed freely. Today, those nations are at a turning point and their cooperation is complicated. This poses many problems: the water supply is dwindling and dry periods are more regular, challenging the economy of these countries which is largely based on agriculture.

One particular issue is worsening the water crisis in Central Asia: the desertification of the Aral Sea.

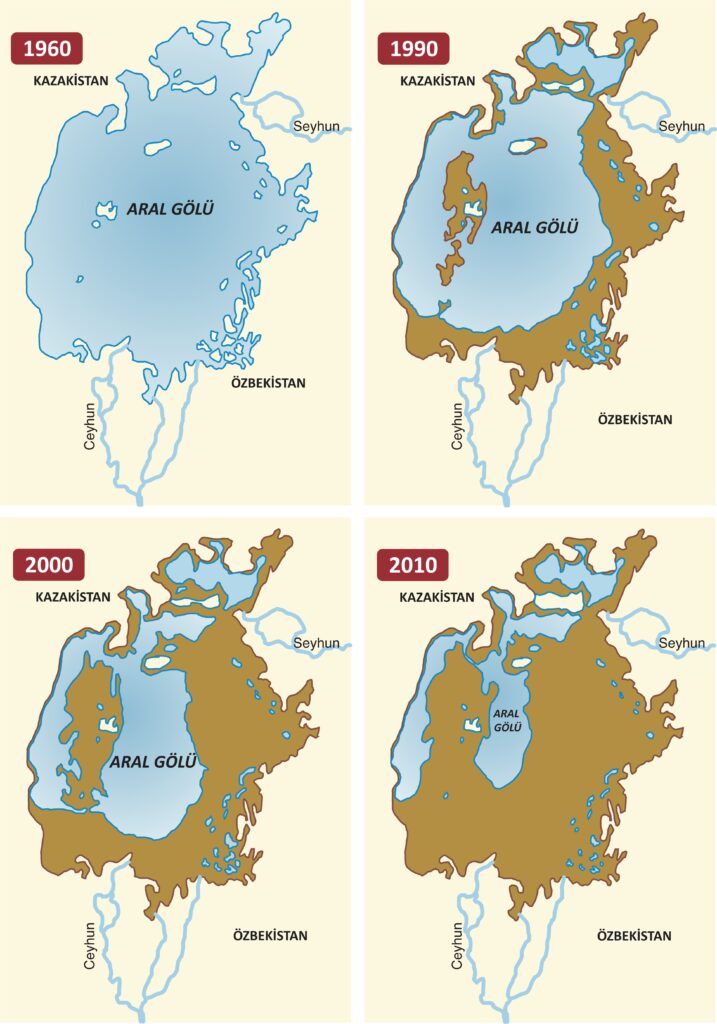

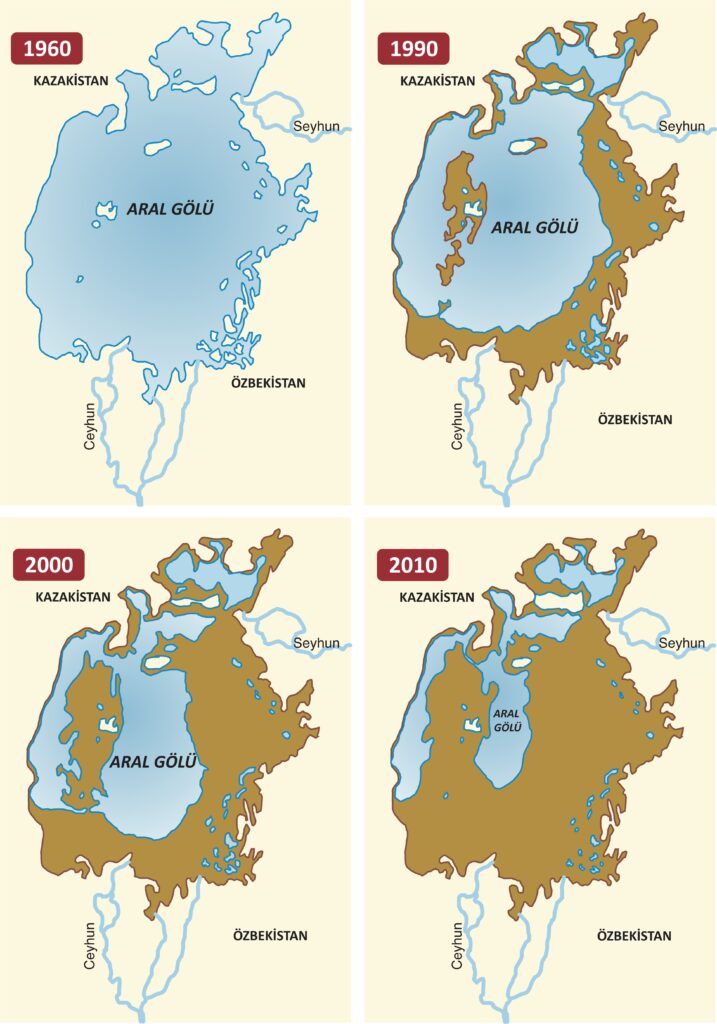

Indeed, the Aral Sea, which is in fact a lake, represents one of the most pressing human-caused ecological disasters in the world. The lake, which used to be the 4th largest in the world, fed by the Amu Darya and Syr Darya rivers, has lost 75 percent of its surface area and 90 percent of its water volume within 50 years. In the past, villages, towns and people prospered and lived in the lush area, the fishing industry was strong and biodiversity was preserved. Today, most parts of what used to be a massive lake are entirely dried out.

The turndown began in 1960 when the Soviet Union started the grand-scheme cultivation of cotton in the surrounding arid regions. Ironically, cotton is one of the most water demanding crops. This necessitated the diversion of the rivers feeding the lake to ensure sufficient water supply. The lake was then losing between 20 and 60 cubic kilometers of water per year as the river had reduced drastically. Despite government directives that try to curb the destructive cultivation Uzbekistan and Turkmenistan are still growing cotton and rice. However, the cultivation decreased due to the diminishing rivers, once filled by the Aral Sea and the surrounding glaciers.

The process of heavy irrigation, unsuited to support intense agriculture, has led to a sharp increase in salinity and waterlogging. Today, most parts of the lake have turned into barren desert. The once lush and flourishing ecosystem is now severely ill. Caused by the salinity and pesticides accumulated at the bottom of the basin, millions of fish died and many species disappeared from the lake. This disrupted the climate patterns of the region, making winters colder and summers hotter – the latter requires even heavier irrigation.

In the surroundings of the lake the once successful fishing industry completely collapsed. Those people who have not left the area yet face great challenges like desertification and unemployment. In addition, more frequent sandstorms and winds carrying pesticides into the air have contaminated the population. This led to a big increase in the incidence of cancer and respiratory diseases. Today, infant mortality in the region is among the highest in the world.

A future for the Aral Sea

Not all hopes are lost yet in the Aral Sea. Even damage of such proportions can be reversed with investment and international cooperation. In 2005, the World Bank and Kazakhstan invested in the construction of a 13-kilometer dam to raise the water level and lower the salinity to allow fish to repopulate the lake. Five years later, the northern Aral Sea had risen by 20 percent and the salinity greatly decreased. Today, in the North Aral Sea, birds and fish are filling the shores, fishermen are resettling and although this process may still take a long time, life is slowly starting to return.

However, other parts of the lake are not in the same situation, such as the South Aral in Uzbekistan. The inflow of this much larger part is restricted by dams and almost completely dry. It was deemed impossible to save. Scientists are working hard to find new solutions to rescue this part and allow biodiversity to re-establish itself.

From desert to oasis

On the Uzbek side, the goal is to rebuild biodiversity in order to recover the lost oasis. Many solutions are being conceptualized: The World Bank launched a competition funded by the Central Asia Water and Energy Program in November 2020. The objective is to create and gather new innovative solutions to restore the ecosystem, revitalize the economy, and reverse the human-made disaster and climate change in the region.

Two winning projects emerged from this competition: The Uzbek horticulturalists and botanists Natalya Akinshina and Azamat Azniv want to introduce honey gardens. As the climate is arid, the solution is to plant dry-tolerant plants that flower most of the year in order to attract bees and other insects to re-pollinate the area. This is supposed to improve the quality of the severely degraded soil, limit sandstorms, create jobs and promote green businesses.

“We are just ordinary people who are passionate about bringing life back to the Aral Sea. This recognition will help us realise our dreams of transforming this region from the desert that it currently is into an oasis, one plot at a time.”

Natalya Akinshina

The second winning project is in Tajikistan. It involves creating a learning hub for women in the rural Sughd province where the Syr Darya River used to irrigate the lake. The objective is to educate women about alternative irrigation and farming techniques, exchange knowledge and teach methods of water conservation. Investment in education is often the key to success and allows regions to be saved at a lower cost. This particular project would also raise the status of women and their decision making capacity in a highly unequal region.

The ecological disaster in the Aral Sea continues to have devastating effects on the region, its biodiversity and its people. But nothing is lost yet in the Aral Sea. International cooperation and the promising projects already in place give hope, especially for the North Aral. Still, major efforts and fruitful cooperation of the affected countries are needed to restore the former glory of the lake.

Lucile Corcoran