This article is an opinion piece and its contents represent the standpoint of its author, not UPF Lund or The Perspective’s editorial board.

Just a month ago and for the first time in US history, a former president, Donald Trump, was arrested for 34 counts of felony. In the same month Rishi Sunak, the UK Prime Minister, announced a plan to stop refugees on small boats from legally claiming asylum, a direct challenge to the European Convention on human rights. While in Russia, Putin continues to attack Ukraine, as the civilian death toll has risen to over eight thousand.

What do all three of these recent political events have in common despite being a direct challenge to legal systems and showing a lack of basic human empathy? The connection that is never made by mainstream media is that men were at the forefront of all these decisions or the decisions that resulted in these events. It is never asked if men are simply too dangerous to hold political office. Why is it then when similarities are drawn between the political decisions made by women at the top, these are categorised as a result of their gender?

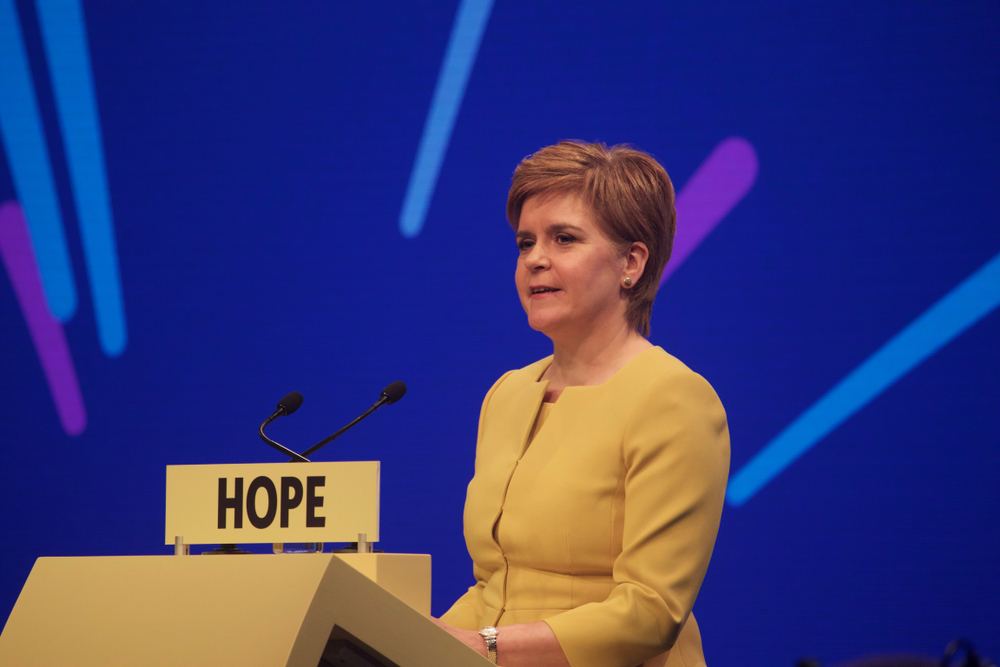

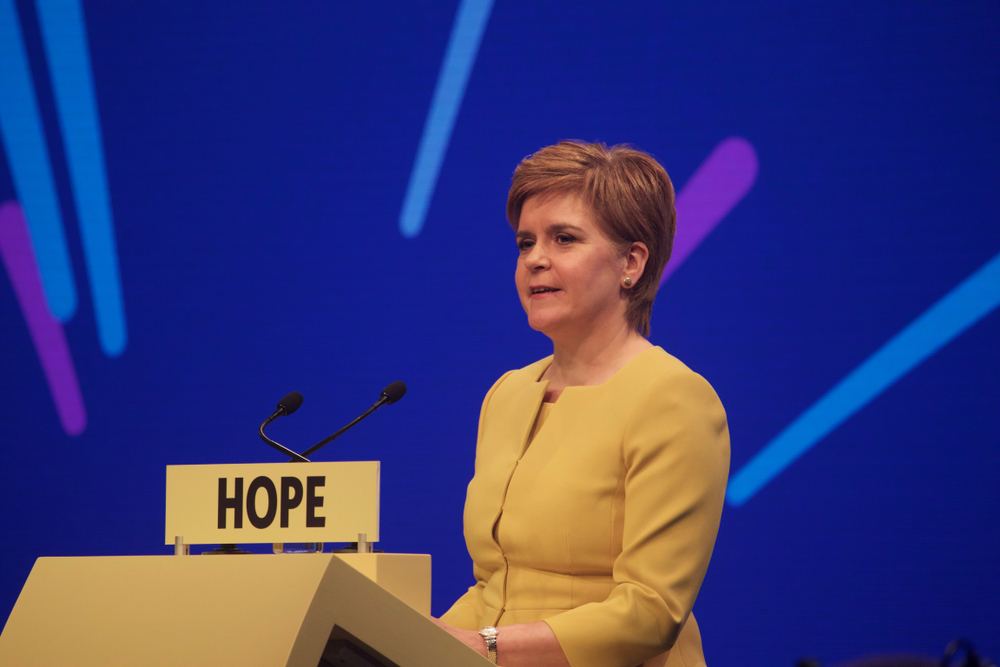

On the 19th of January this year Jacinda Arden, former Prime Minister of New Zealand, announced her resignation naming burnout as one of the central reasons for her departure from the role. Just two months later Nicola Sturgeon, former First Minister of Scotland, also penned her resignation, describing how the lack of privacy, harassment on social media and nature of personality politics became too much to handle. After stating similar reasons for leaving their posts, both Arden and Sturgeon were coupled, seen as representative of their whole gender’s experience of political involvement. Why was this the case? Perhaps it is due to the lack of examples of females holding political power.

While in 2023 women hold the largest recorded number of political decision-making posts worldwide, this does not amount to much when compared to the proportion of men taking positions of power. Only 13 out of the 193 UN member states have a female leader, and the growth of female representation in global politics has slowed down in 2023. As mentioned before, recently a number of female political leaders quit their high-powered posts due to burnout, to later be replaced by men. This plateau in female representation suggests that the current political environment is not conducive to being a woman and holding power. But how can this political environment be changed to equally represent our whole society, allowing change to be made that benefits everyone?

This phenomenon of burnout is not a new one, neither is it exclusive to politics. Being defined as extreme physical and emotional exhaustion, it was included in the World Health Organisation’s 2019 International Classification of Diseases. Trends show that women experience this condition more than men and the examples seen in Arden and Sturgeon must not be ignored. A 2022 study by McKinsey revealed that ‘women leaders are overworked and under-recognized’, as 43% of women leaders compared to only 31% of men at the same level report feeling burnt out.

However, the question of how this is addressed remains. It would be incorrect to understand negative experiences of women in leadership roles as a result of them being women, simply because there is a trend in female experience. Dr Federica Caso, an International Relations lecturer at La Trobe University, is quoted in The Guardian highlighting how ‘It’s hard to keep swimming against the flow when you’re constantly being challenged on your gender, as opposed to your policies’. This is an acute revelation of the issues faced by women when taking up positions of power, as they are seen first for their gender and then their decision-making.

Undoubtedly an increase in female representation is necessary to allow women, once they are in politics to act unthinking of how their gender will be perceived by others. In order for this to be achieved however public attitudes and actions towards female politicians must also be changed. Coping with constant online threats and sexist abuse is simply part of the job for women who hold political power. A study from the Fawcett Society published in January 2023 found that 93% of female members of parliament (MP) in the UK said online abuse had a negative impact on them, compared with a much lower 76% of men. While a symptom of the sexist society we still operate in, this abuse is also a clear obstacle to an increase in female political representation. However, it is not just the public which must change if we wish to see more women in politics. The same Fawcett Society report found that two-thirds of women MPs have witnessed sexist conduct from within Parliament. While revealing the lack of support women felt once involved in the political sphere from their male counterparts, these figures are also telling of the high rates of burnout experienced by women once holding high power positions.

How can we change the culture of politics, thus increasing the number of women involved and as a result stopping a few women from being representative of all women? A common strategy used by countries to try and achieve equal representation is introducing a gender quota reform. This allows for a fast-tracked increase in women in politics, as a certain percentage of women is typically required to be involved in a political decision-making body. The introduction of these quotas has resulted in huge changes in which countries have the largest female parliamentary representation. Whilst in 2000 Sweden, Denmark, Finland and Norway held the top spots respectively, just two decades later Rwanda has beaten Sweden off the top spot as 61.3% of their parliament is made up of women. The African country is followed by Cuba, Bolivia and the United Arab Emirates (UAE) revealing just how powerful quotas may be in increasing female representation. Therefore, quotas are arguably one of our most powerful resources for gender equality in politics. Once more women are involved in politics, they may influence policy change to benefit women. A study on Argentine politics from Franceschet and Piscopo in 2008 found that ‘the number of women’s rights bills increased substantially following the implementation of a gender quota’, as it is only when everyone is represented equally in politics that political decisions may truly benefit the whole society.

Women entering into politics has undoubtedly revealed new things about our political systems, as women may react differently to stresses that men take for granted. While the recent resignations of Arden and Sturgeon give vital recognition to the impacts of mental health issues in the workplace, the disparity in rates of experience between men and women is important to address. It is necessary however to understand that Arden and Sturgeon’s experiences are symptoms of a political system which favours men, not a symptom of being a woman. Therefore the system must be changed, whether this is through quotas, education or repeated encouragement, an increase of women in politics is imperative to improve politics for women.

By Maia Appleby Melamed